Hidden Barriers IV

SuperStudio 1

Dr David Coyles, Senior Lecturer in Architecture: Studio Lead

Eduardo Rebelo, Lecturer in Architecture: Studio Support

HIDDEN BARRIERS looks at the unseen ways in which the forces of conflict shape urban space and community development. It considers ‘conflict’ as something that emerges in many forms and concerns with the impacts of social conflict, economic conflict, environmental conflict, and political conflict. As the opening quotation from Calvano’s Invisible Cities suggests, the studio attempts to look beneath the surface of everyday appearances and to reveal, unpack - and perhaps begin to understand - some of the hidden complexities that make up the everyday urban spaces that we so often take for granted.

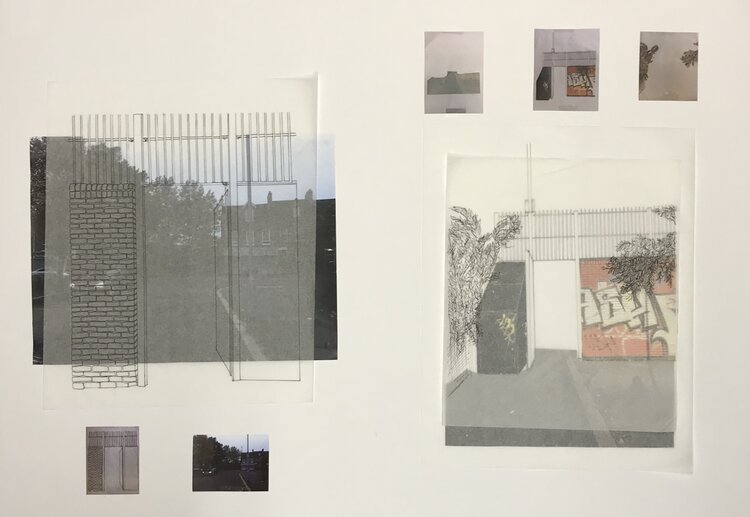

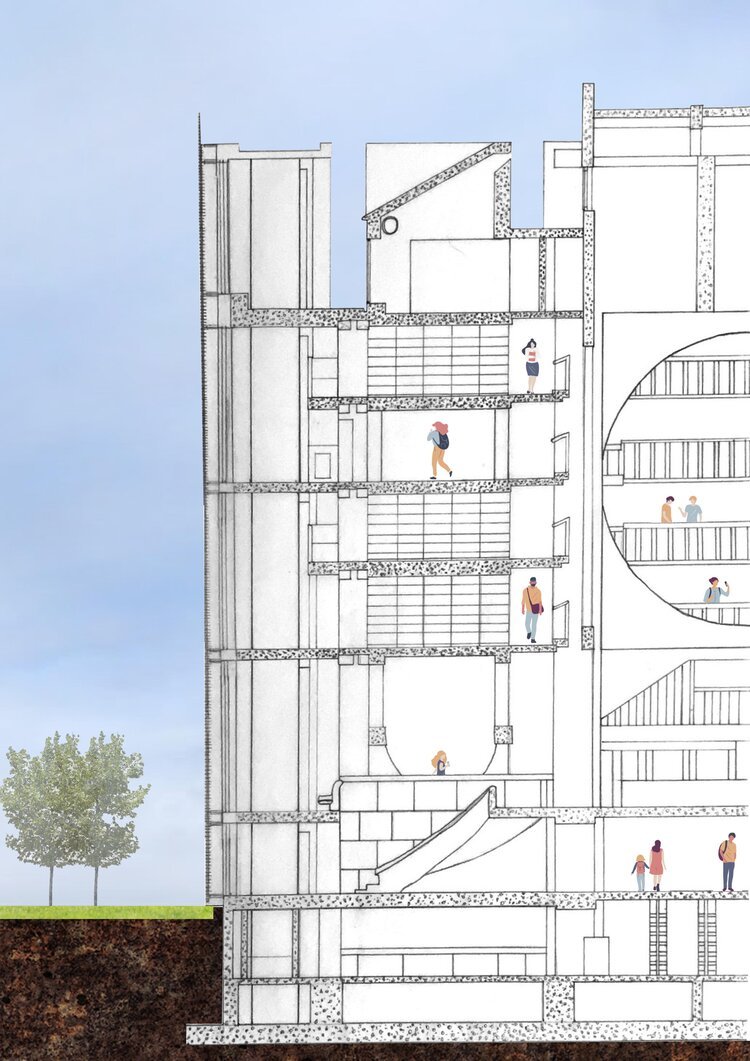

The studio draws upon active research findings emerging from the Ulster University Hidden Barriers research programme which is underpinned by a series of projects funded by the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC). Hidden Barriers uses this multidisciplinary research base to explore innovative and cross-disciplinary methods of charting, analysing, and mapping urban landscapes and proposing thoughtful architectural propositions. We make creative use of drawing, photography, video, and a wide range of digital-software techniques - and we place a strong emphasis on the use of physical and digital models to communicate our design thinking, design process and architectural proposals.

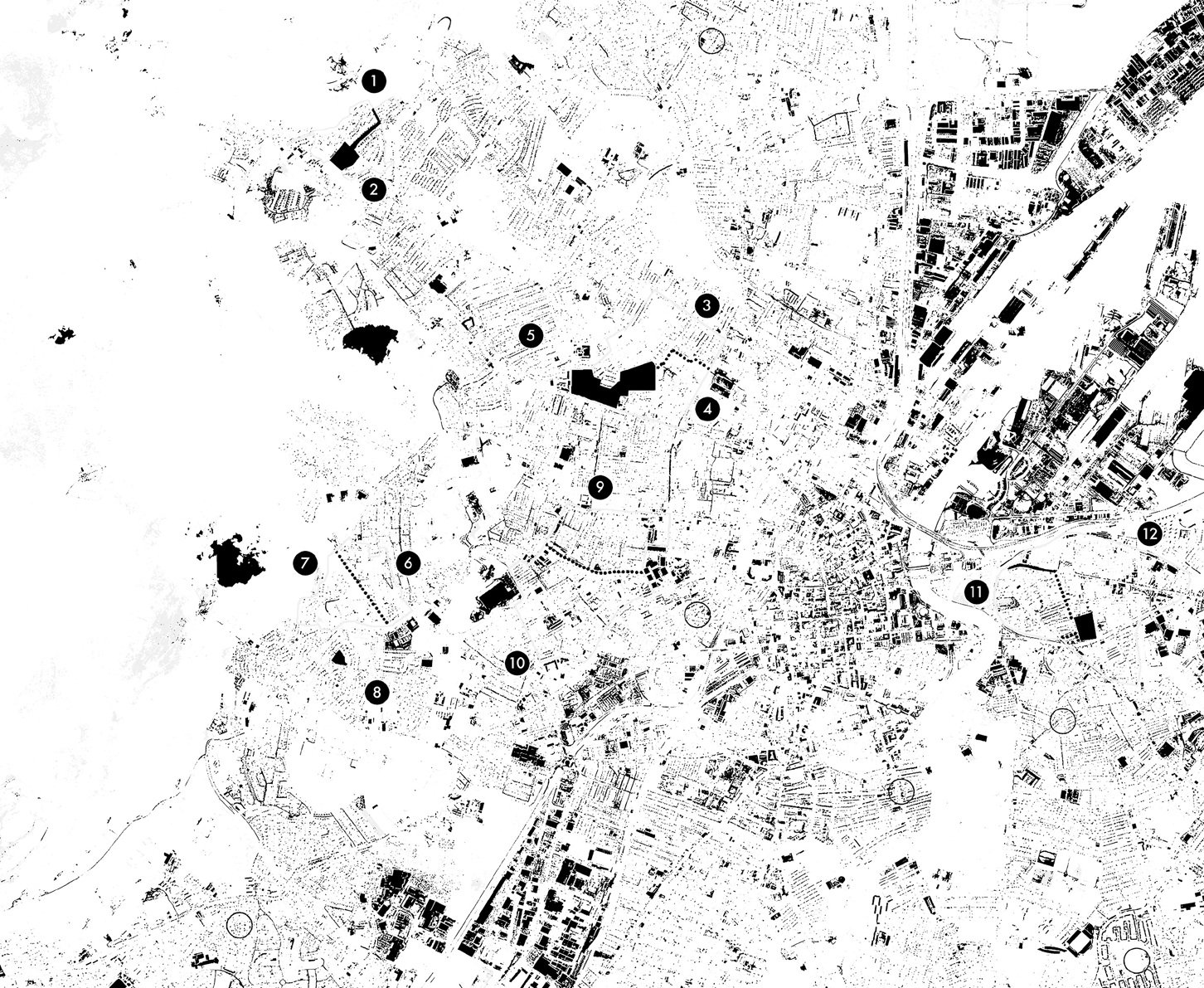

Architectures of Inequality is the overarching theme that guides the range of projects making up what is now the fifth iteration of the Hidden Barriers superstudio. The studio is interested in shining a light on the less understood role that the everyday architectures and spaces of communities plays in fostering inequalities and the many different and contrasting forms that these inequalities might take. Belfast acts as a primary Semester 1 case study that is investigated and analysed and then compared with a series of international cities currently under investigation by the Hidden Barriers research programme. By understanding the ways in which the architectural and spatial legacies of conflict in Belfast have embedded hidden inequalities within many communities in Belfast, our discussions and debates will be informed by insights and perspectives gleaned from a range of Semester 2 investigations within international cities impacted by quite different forms of social, economic, political, and environmental conflict: Detroit in the United States; and Bilbao in the Basque Country.

Calvino’s fables are evoked through fictive rendering of myth and legend where the application of meaning is at the behest of the storyteller. The capacity for alternate (and perhaps equally valid) descriptions of architecture prompts an interesting consideration as to whether these tales were works of the imagination or, rather, adroit interpretations of Venice manifest in its bricks, stones, mortar, water and earth. In this sense a conceptual connection can be drawn with the city of Belfast.

Like Calvino’s Invisible City, Hidden Barriers theorises Belfast as a Hidden City enjoying competing and conflicting interpretations of its architecture that camouflage its full quintessence and ultimate importance. Viewed through the emotive lens of a city emerging from the Troubles which raged between 1969 and 1994, the studio discussions pertain to the imaging (not imagining) of architecture as something other than what it first might appear to be, or perhaps, something different altogether.

Belfast

The decision to impose Hidden Barriers in Belfast can be traced back to two significant processes coming together between 1976 and 1977. On the one hand, there was the dilapidated state of the inner-city terraced housing stock. This dense gridiron of Victorian terraced houses which characterised the inner-city has been in existence since the late 19th C and early 20th C and had been built to house the workforce associated with the city’s rapid industrial expansion. In common with many industrialized cities across the UK, the condition of Belfast’s 19th century housing stock deteriorated rapidly during the opening decades of the 20th century. By 1976, government surveys deemed Belfast to have the “worst housing stock in the UK and possibly in Western Europe.” On the other hand, there was the impact that conflict was having on people living within these houses. Since the industrial era, inter-communal violence would routinely break out between Catholic and Protestant groups in residential areas when wider national political tensions were high. A gradual consolidation of the city into Catholic and Protestant territories was massively exacerbated by the outbreak of the Troubles in 1969. Between 1969 and 1976, over 15000 people in Greater Belfast were thought to have fled their homes in response to sectarian violence and “direct intimidation” or “fear of intimidation” from paramilitary groups. Historic inequalities in the development of housing across Northern Ireland meant that the options for Catholic and Protestant residents contrasted significantly. This led to a paradoxical situation where the housing authorities were recording both a surplus of housing and a waiting list for housing. For example, in north Belfast alone, 3000 Catholics were registered on the official waiting list for housing in 1976 whilst surplus housing in north Belfast was also being recorded as in excess of 10,000 dwellings.

To deal with this dilemma two processes would be put in place in 1977 to manage the situation. In keeping with similar initiatives taking place in other former major industrial cities such as Glasgow and Liverpool, the government announced a sweeping programme of inner-city redevelopment for Belfast. Shortly thereafter, the government would also establish a confidential Standing Committee on the Security Implications of Housing Problems in Belfast to work alongside the redevelopment programs but outside of public view. The coming together of these public and private processes would give Belfast its first purpose-built physical divisions between Catholic and Protestant areas. Some of these are highly visible and widely recognised, such as Belfast’s major peace wall installations. However, the Hidden Barriers also put in place by the committee are much more problematic. In stark contrast to the visibility of the peace walls, these Hidden Barriers use ‘everyday’ elements of the built environment such as shops, offices, factories, roads, and landscaping to separate and isolate communities. In this way, they almost hide in plain sight across the contemporary city.

Detroit

Once the fourth largest city in the USA and a rich and powerful hub for economic activity that centred on the automotive industry, decades of outward migration, disinvestment and social change have ravaged the city, creating images of inner-city desolation and abandonment on a scale not thought possible within the developed world. The abundance of vacant, unwanted space is such that it has become home to ‘urban farming’, with acres of crops now occupying ground that was once prime real-estate. More starkly put, the entire urban core of the city of San Francisco, USA, could be fitted within the vacant space that exists within present-day Detroit. To help understand the different ways in which the material visibilities of social and economic conflict remain very visible, we will collaborate with Detroit scholars based at the University of Oregon and Wayne State University, Detroit.

Bilbao & The Basque Country

Once deemed to be the ugliest city in Spain, Bilbao is now regarded as a chic, cosmopolitan cultural capital and frequently championed as the glowing success story of architecturally led urban regeneration. Much of this success is attributed to development of the iconic Guggenheim Museum and the international recognition that this had brought to Bilbao. What is much less understood, is that far from being the catalyst for this success, the Guggenheim Museum is better understood as the culmination of a sustained twenty-year redevelopment programme that gradually transformed the city through clever use of economics, planning and management. Also less understood are the underlying cultural and territorial tensions that are often masked by the shiny visage of this now famous museum. We will have the opportunity to collaborate with colleagues at the University of the Basque Country to try and understand how the forces of gentrification are becoming powerful drivers of emerging inequalities between the new redeveloped city and those parts still waiting to benefit fully from the newfound investment.

STUDIO RESEARCH STATEMENT

Research Content and Process

Hidden Barriers considers architecture in its widest sense and our examinations are particularly interested in the less visible ways that conflict manifests itself in ‘everyday’ urban space. Whilst ‘spatiality’ and ‘architecture’ have become recognized as important dimensions of urban conflict, contemporary forms of power push our gaze towards symbolic landmarks such as Belfast’s ‘peace walls’. The Hidden Barriers SuperStudio uses Belfast as a case-study to instead highlight the fundamental role occupied by ‘everyday’ urban space and architecture. It reveals evidence of an undisclosed body of divisive architecture put in place through a confidential process of security planning between 1978 and 1985 to physically segregate and spatially fragment Catholic and Protestant communities in contested areas of Belfast. Termed by the research as ‘hidden barriers’, they are formed from ‘everyday’ roads, housing, shops, offices, factories and landscaping, and the ways in which they continue to promote division represents a crucially undervalued aspect of conflict-transformation planning. The SuperStudio examines the complex urban challenges that they pose, arguing for a re-evaluation of the role of everyday architecture and space in conflict and peacebuilding processes.

Description

Hidden Barriers considers architecture in its widest sense and our examinations are particularly interested in the less visible ways that conflict manifests itself in ‘everyday’ urban space. Whilst ‘spatiality’ and ‘architecture’ have become recognized as important dimensions of urban conflict, contemporary forms of power push our gaze towards symbolic landmarks such as Belfast’s ‘peace walls’. The Hidden Barriers SuperStudio uses Belfast as a case-study to instead highlight the fundamental role occupied by ‘everyday’ urban space and architecture. It reveals evidence of an undisclosed body of divisive architecture put in place through a confidential process of security planning between 1978 and 1985 to physically segregate and spatially fragment Catholic and Protestant communities in contested areas of Belfast. Termed by the research ‘hidden barriers’, they are formed from ‘everyday’ roads, housing, shops, offices, factories and landscaping, and the ways in which they continue to promote division represents a crucially undervalued aspect of conflict-transformation planning. The SuperStudio examines the complex urban challenges that they pose, arguing for a re-evaluation of the role of everyday architecture and space in conflict and peacebuilding processes.

Research Questions

The overarching aim of this research is to effect material change in the community life of some of Belfast’s most deprived urban areas. The studio therefore places an emphasis on helping to help make the contemporary effects of what we term ‘Hidden Barriers’ more visible, so that we can begin to have meaningful discussions and debates about their continued presence and impact. This suggests three questions:

What do these Hidden Barriers look like?

Where are they located? What urban areas are affected? What specific types of buildings, structures and spaces are involved?

What do communities have to say about this architecture?

What are the experiences of residents? What problems do they perceive? What changes would they like to see?

How can this research inform the related and relevant policy discussions?

What barriers and forms of physical division are currently under the scope of the ‘united community’ policy umbrella and which are not?

Methods

Our investigations employ multidisciplinary methodologies drawn from the underpinning Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded research projects. However, there is a primary emphasis placed on the gathering of evidence through core practice-based architectural fieldwork and the related tactics of observation, drawing and model-making. These are supplemented by site-based video and photography. All investigations are typically underpinned by a mix of archival research, qualitative interviews and literature reviews.

Findings and Outlook

The research suggests three typologies of hidden barriers which act at different scales and in different ways to promote social and physical division. At the first level, there are Inter-Community Barriers. These are instances of the built environment being used on a larger scale to separate two communities that were connected through the urban fabric before the onset of redevelopment in 1977, effectively leaving them fixed and isolated as ‘single-identity’ areas. At the second level, Intra-Community Barriers are instances where the redevelopment proposals within these single-identity communities have transformed the existing network of interconnected terraced streets into spatially fragmented and disconnected clusters, creating urban areas that are extremely fractured and difficult to navigate. The third level of hidden barriers are what we call Invisible Boundaries. These barriers are not a direct consequence of the redevelopment programs or security-orientated government intervention. Rather, they are elements of public space on the periphery of other hidden barrier areas that are identified locally as a recognised ‘boundary’ between the two communities, which has evolved at a local level and become entrenched over time.

Dissemination

The research findings have informed a range of publications (Coyles 2013, 2017a, b; Coyles 2018; Coyles, Hamber and Grant 2018; Coyles, Spier and Wylie 2013; Wylie and Coyles 2018). The findings have also been the subject of international workshops and policy symposia in Detroit, San Diego, the Basque Country, Sweden and the Netherlands. In 2018, the findings were presented at the Northern Ireland Assembly Knowledge Exchange Seminar Series (KESS).

SuperStudio Imagery

For more information on this SuperStudio, please contact David Coyles